Dense-packing Fiasco

My comment on a post here: https://jackdevanney.substack.com/p/the-dense-packing-fiasco

Jack, I would post this as a comment on the Dense-packing Fiasco post, except I can’t put pictures in a post.

In the first paragraph of the discussion you say:

“The obvious fallback was on-site dry cask storage. But dry cask storage adds about 0.1 cents per kWh to the cost of the electricity.”

This not only makes it sound like this is a nuclear electric utility manufactured problem, but also has an incorrect statement of “obvious fallback” being some sort of earlier solution.

The Federal Government caused this problem, and in fact even owns the fuel (both new and used). The obvious solution was to tell (and force) them to come and get their used fuel. The government agreed to and the AEC approved plan at the time these utilities decided to build a nuke plant in the first place, was that the utilities would not be long term responsible for the government’s used fuel. This was the general understanding by utilities buying nuclear power plants at that time. The Federal government even was encouraging utilities to go nuclear via programs like “Atoms for Peace”. It’s likely no commercial nuke plants would ever have been built in the first place had they known this was going to happen.

The construction of the Davis Besse Nuclear Power Plant began officially on Sept 1 1970. That means the AEC would have issued them a 10CFR Part 50 Construction Permit, based in part, on the facility description in the plant in the Preliminary Safety Analysis Report (PSAR). This PSAR described the proposed Spent Fuel Storage, cooling, support systems, and handling process. This Spent Fuel Pool had a capacity of 260 spent fuel elements. And remember, these plants were licensed to run for 40 years.

The next construction picture shows the location of the Spent Fuel Pool in what would be the Auxiliary Building, outside of the Containment Building.

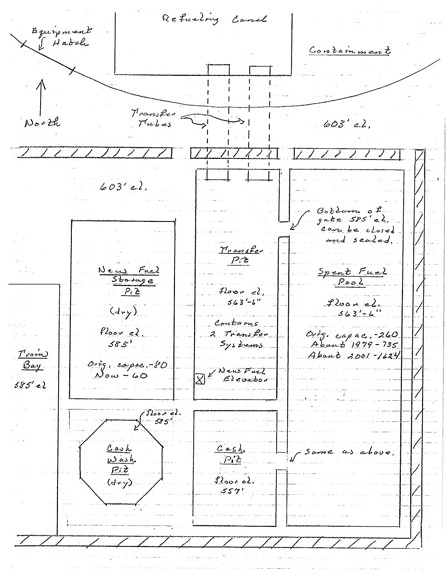

The next picture is a sketch of the Fuel Handling Building new and used fuel handling areas. Note the cask pit, and cask wash down areas, and also the RR Train Track area into the building.

Dense-packing FiascoSo how did that 260 Fuel Assembly Spent Fuel Pool work, by the numbers. Davis Besse was a 177 Fuel Assembly Babcock and Wilcox PWR running on 12 month refueling cycles. Each refueling cycle about one third of the fuel assemblies would be replaced, for simplification say 60 FAs. Then a new fuel cycle would start. If some problem arose during the cycle there was still room in the SFP to completely off load the whole core if needed. Before the end of that fuel cycle the US Government would come and get THEIR fuel (DB would load it in the shipping cask for them) and they would take it away and do whatever they planned to do with THEIR spent fuel (wink, wink). And so on and so on.

By about 1979 Davis Besse had increased the capacity of their SFP to 735 Fuel Assemblies. At about 60 FAs per refueling it’s not hard to do the math on how long it took to fill the SFP (for a 40 yr design life plant).

By about 2001 Davis Besee had increased the capacity of their SFP to 1624 FAs using “dense-packing” racks.

So what changed?

In 1974 Congress passed the Energy Reorganization Act of 1974, which assigned the AEC functions to two new agencies: the Energy Research and Development Administration and the Nuclear Regulatory Commission.

October, 1976, President Ford issued a Presidential Directive to indefinitely suspend the commercial reprocessing and recycling of plutonium in the U.S.

At this point the Federal Government had essentially plugged up the butt of every commercial nuke plant, once their SFP was full.

April 1977 President Carter banned the reprocessing of commercial reactor spent nuclear fuel.

On August 4, 1977, President Carter signed into law The Department of Energy Organization Act of 1977, which created the Department of Energy. The new agency assumed the responsibilities of the Federal Energy Administration, the Energy Research and Development Administration, the Federal Power Commission, and programs of various other agencies.

March 28, 1979, Three Mile Island Unit 2 partially melts their reactor core.

In 1981 President Reagan lifts the ban on reprocessing used nuclear fuel, but did not provide the substantial subsidy that would have been necessary to start up commercial reprocessing.

In 1982 The Nuclear Waste Policy Act of 1982 is passed by congress. The Nuclear Waste Policy Act required the Secretary of Energy to issue guidelines for selection of sites for construction of two permanent, underground nuclear waste repositories. DOE was to study five potential sites, and then recommend three to the President by January 1, 1985. Five additional sites were to be studied and three of them recommended to the president by July 1, 1989 as possible locations for a second repository. A full environmental impact statement was required for any site recommended to the President. Locations considered to be leading contenders for a permanent repository were basalt formations at the government's Hanford Nuclear Reservation in Washington; volcanic tuff formations at its Nevada nuclear test site, and several salt formations in Utah, Texas, Louisiana and Mississippi. Salt and granite formations in other states from Maine to Georgia had also been surveyed, but not evaluated in great detail. The President was required to review site recommendations and submit to Congress by March 31, 1987 his recommendation of one site for the first repository, and by March 31, 1990, his recommendation for a second repository. The amount of high-level waste or spent fuel that could be placed in the first repository was limited to the equivalent of 70,000 metric tons of heavy metal until a second repository was built. The Act required the national government to take ownership of all nuclear waste or spent fuel at the reactor site, transport it to the repository, and thereafter be responsible for its containment.

The Act established a Nuclear Waste Fund composed of fees levied against electric utilities to pay for the costs of constructing and operating a permanent repository, and set the fee at one mill per kilowatt-hour of nuclear electricity generated. Utilities were charged a one-time fee for storage of spent fuel created before enactment of the law. Nuclear waste from defense activities was exempted from most provisions of the Act, which required that if military waste were put into a civilian repository, the government would pay its pro rata share of the cost of development, construction and operation of the repository. The Act authorized impact assistance payments to states or Indian tribes to offset any costs resulting from location of a waste facility within their borders.

In 1984 In 1984 the NRC adopted the original Waste Confidence Decision and Rule (10 CFR 51.23).

Also in 1984, December 19, 1984, the Department of Energy selected ten locations in six states for consideration as potential repository sites. This was based on data collected for nearly ten years.

April 26, 1986, Chernobyl Nuclear Accident.

In 1987, December, 1987, Nuclear Waste Policy Amendments Act. In December 1987, Congress amended the Nuclear Waste Policy Act to designate Yucca Mountain, Nevada as the only site to be characterized as a permanent repository for all of the nation's nuclear waste. The plan was added to the fiscal 1988 budget reconciliation bill signed on December 22, 1987. Working under the 1982 Act, DOE had narrowed down the search for the first nuclear-waste repository to three Western states: Nevada, Washington and Texas. The amendment repealed provisions in the 1982 law calling for a second repository in the eastern United States. No one from Nevada participated on the House-Senate conference committee on reconciliation. The amendment explicitly named Yucca Mountain as the only site where DOE was to consider for a permanent repository for the nation's highly radioactive waste. Years of study and procedural steps remained. The amendment also authorized a monitored retrievable storage facility, but not until the permanent repository was licensed.

In 1990 NRC issues Spent Fuel Storage Cask Approval. Congress approves the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act (OBRA-90) which requires the NRC to recover 100% of the NRC budget from fees on licensees.

Early in 2002 the Secretary of Energy recommended Yucca Mountain for the only repository and President Bush approved the recommendation. Nevada exercised its state veto in April 2002 but the veto was overridden by both houses of Congress by mid-July 2002. In 2004, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit upheld a challenge by Nevada, ruling that EPA’s 10,000-year compliance period for isolation of radioactive waste was not consistent with National Academy of Sciences (NAS) recommendations and was too short. The NAS report had recommended standards be set for the time of peak risk, which might approach a period of one million years. By limiting the compliance time to 10,000 years, EPA did not respect a statutory requirement that it develop standards consistent with NAS recommendations. The EPA subsequently revised the standards to extend out to 1 million years. A License Application was submitted in the summer of 2008 and is presently under review by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission.

The Obama Administration rejected use of the site in the 2010 United States Federal Budget budget, which eliminated all funding except that needed to answer inquiries from the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, "while the Administration devises a new strategy toward nuclear waste disposal." However, the NWPA is still the federal law and is not a project of the President and cannot be canceled by either President Obama or the Energy Secretary. On March 5, 2009, Energy Secretary Steven Chu told a Senate hearing the Yucca Mountain site is no longer viewed as an option for storing reactor waste. In Obama's 2011 budget proposal released February 1, all funding for nuclear waste disposal was zeroed out for the next ten years and it proposed to dissolve the Office of Civilian Waste Management required by the NWPA. In late February 2010 multiple lawsuits were proposed and/or being filed in various federal courts across the country to contest the legality of Chu's direction to DOE to withdraw the license application. These lawsuits were evidently foreseen as eventually being necessary to enforce the NWPA since Section 119 of the NWPA provides for federal court interventions if the President, Secretary of Energy or the Nuclear Regulatory Commission fail to uphold the NWPA.

As a retired nuke plant employee I take it as kind of an insult to read the utilities caused this Dense-pack problem to save a few bucks. After 47 yrs of commercial operation Davis Besse is still waiting on the Federal Government to come and get even one of THEIR spent fuel assemblies.

Mike Derivan (mjd)

Here's a link to proof the the US Government owns the Spent Fuel and even has to pay the utilities to store it. It's a breach of contract for the government not to take their Spent Fuel and proven in a court of law: https://www.buildsmartbradley.com/2024/08/united-states-ordered-to-pay-breach-of-contract-damages-to-nuclear-operator-in-spent-fuel-dispute/